by Paul Rosenberg – FREEMANSPERSPECTIVE

It’s over. Except for a short moment or a wild and self-exhausting governmental mandate (both of which are doubtful), there will never again be enough “good jobs” to go around. That model is gone and we need to root it out of our imaginations.

Sure, there will be some good jobs, but nowhere near enough.

About half of the Western world is already on the dole in one form or another. 93 million Americans lack a decent job and have no real hope of getting one. And so long as the current hierarchies remain, things won’t get substantially better.

I’m sorry to dump that on you, but it’s better to face it directly.

But please bear in mind that I’m a confirmed optimist. Just because there are no “good jobs” doesn’t mean that we’ll all languish in a meaningless existence. Far from it. Once we get over our addictions to status, hierarchy, and dominance, a glorious future awaits us.

Why It Won’t Get Better

The standard response to what I’ve noted above is to call it “the Luddite fallacy.” That line of argument says that in the past, innovation has not wiped out jobs, that new types of jobs were created and filled the gaps fairly well.

And that statement is true. Individual jobs were wiped out, but new jobs came along and (more or less) picked up the slack.

However, that is not happening this time, and for a very simple reason: Adaptation is now against the law. Previous rises in technology occurred while adaptation was still semi-legal.

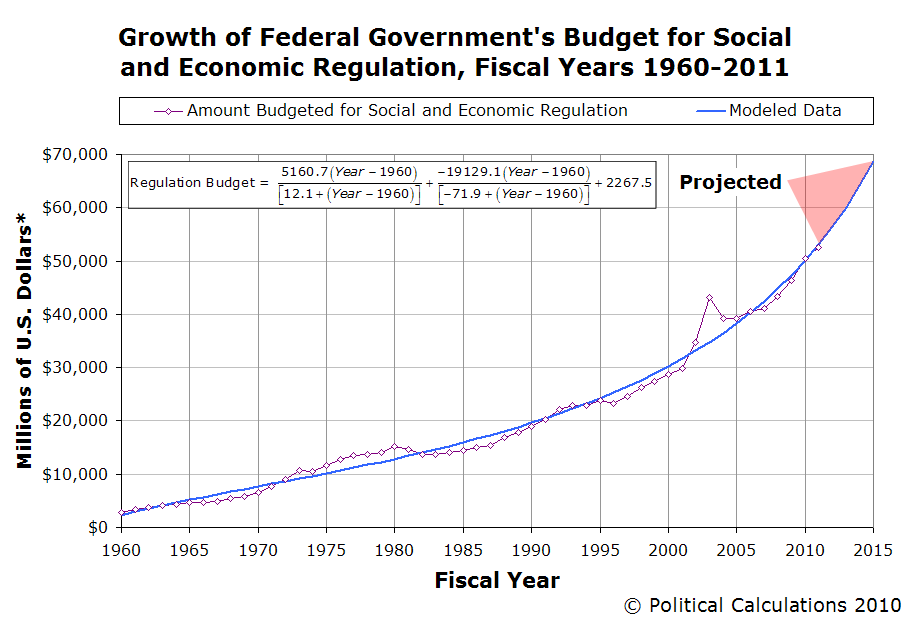

Please take a look at this graph and remember a simple truth: Regulation forbids adaptation.

The US government is currently spending $60 billion, every year, to restrain business activity. (And the EU is worse.) On top of that, reasonable estimates show that US government regulations cost businesses nearly $2 trillion per year.

And let’s be honest about this: The primary purpose of regulation is to give the friends of congressmen a business advantage. Why else would they pay millions of dollars to lobbyists?

So, the new jobs that should be spawned, will not be. Mega-corps own Congress and they get the laws they pay for. And mega-corps do not like competition.

Furthermore, the political-corporate-bureaucratic complex will bite and claw to retain every scrap of power they have, and small businesses will be their first victims. (They already are.)

Trapped Between Hammer and Anvil

So, the people who are hoping and waiting for a “good job” to pop up are trapped between hammer and anvil. Robots are starting to roll into the workplace while the job creators (small entrepreneurs) are in regulatory and economic chains. They can’t come to the rescue.

In the 19th century, all sorts of possibilities were open to entrepreneurs. This remained at least partly true, even into the 1970s, when I watched the business heroes of my youth having a gas while making piles of money.

It used to be that a clever person could get ahead, independently, and have a ball doing so.

Those days, alas, are over.

These days, to get rich, one needs to take government as a partner. If one does not, regulation and legislation are likely to destroy your business. At this point, many of us (myself included) have had businesses – good businesses that benefited everyone involved – crushed by legislation.

To avoid being crushed these days, you have to be smarter and fleeter of foot than everyone else. Not many of us can survive in that situation, and as regulations continue to rise, even that number grows smaller and smaller.

For the generation before of mine, independent success required ambition, but it was reachable. For my generation, only those of us blessed with unusual talent had a chance at controlling our economic destinies. For the young generation of today, it’s nearly impossible. These days, if you want to jump ahead, you need to be part of something big… and you need to start as a sycophant.

So…

So, if you’re looking for the proverbial good job, stop waiting for “The Hierarchy That Is” to sort things out and get everything back to normal. Good jobs get fewer and fewer every year, and those that are lost won’t be coming back.

But… if and when you’re ready to change your thinking – to seriously change your thinking – this is good news too: You can reclaim the parts of yourself that you were ready to sacrifice to the “good job.”

You see, the “good job” was nearly as much a curse as it was a blessing. Yes, I know, steady wages and benefits are a very comfortable thing, but they also play right into a ridiculous, predatory script.

You know the one: where you struggle to display your status to all the other worker-bees. You feel like you have to do what the ads tell you: Get the new car, the bigger truck, the video player in the back seat, the gigantic TV, the most “amazing” holiday parties, the expensive shoes, the designer bags, the organic veggies, etc., etc., etc.

I would like you, please, to consider this quote from the boss of Lehman Brothers, just as the World War I production surge was failing:

We must shift America from a needs, to a desires culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old had been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.

Would you agree that their plan worked?

As long as you follow their script, you’ll remain in a permanent deficit mentality. No matter how much you have, you’ll always feel like you need more. It’s life on a shiny gerbil wheel. The “good job” kept us from knowing ourselves; it allowed us to sleep-walk through life. We got a “good job” and never developed ourselves any further. Work, retire, die, ho hum.

Then What?

So, if we forget about having a “good job,” what happens?

Well, it might very well mean that you do what you’re already doing, but you stop feeling bad about it. It means that you get over the endless grasping after status… of letting ridiculous ads define what “success” looks like… of letting other people define your self-opinion.

Letting go of the “good job” delusion means that you stop pining for the days when you could blow a third of your money on status crap. It means that you start taking pleasure in growing your own food, developing new ventures, and improving yourself.

It means that rather than begging politicians to ride in on a white horse and fix your world, you ignore them and start paying attention to your actual life.

Fundamentally, this means that we start using our own initiative, without seeking permission, and start building better things.

Rather than going on, I’ll leave you with two quotes, both from Erich Fromm. I think they are worth close consideration:

Our society is run by a managerial bureaucracy, by professional politicians; people are motivated by mass suggestion, their aim is producing more and consuming more, as purposes in themselves. All activities are subordinated to economic goals, means have become ends; man is an automaton – well fed, well clad, but without any ultimate concern for that which is his peculiarly human quality and function.

The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers.

Paul Rosenberg

[Editor’s Note: Paul Rosenberg is the outside-the-Matrix author of FreemansPerspective.com, a site dedicated to economic freedom, personal independence and privacy. He is also the author of The Great Calendar, a report that breaks down our complex world into an easy-to-understand model. Click here to get your free copy.]