Since the founding of the germ theory of disease, scientists have offered a holistic perspective. At long last, their efforts are taking hold.

I grew up in a household afraid of germs. When my sister was born, my father had all guests put on surgical masks to protect her. We all had our tonsils taken out “just because,” and antibiotics were considered a miracle discovered by science. My generation was the one first introduced to fast food—we really believed it was food! Our mothers were sold the idea that formula could be better than breast milk. So began the modern, manipulated, misdirected generation.

Fortunately, before I had my kids, I was introduced to chiropractic. I discovered the body’s amazing intelligence and its innate ability to heal itself. I learned about nourishment, a healthy attitude and a functional nervous system. Among the many teachings of chiropractic’s founder, D.D. Palmer, and his son, B.J., I was most fascinated with B.J.’s comment, “If the ‘germ theory of disease’ were correct, there’d be no one living to believe it.”

Fortunately, my husband and I were able to live the “chiropractic lifestyle” with our kids. Years before the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended breastfeeding (yes, they finally did in the ’90s) we were strong advocates for it. Long before the allopathic healthcare system was recognizing the importance of nutrition, we as chiropractors were recommending and consuming good, wholesome, pesticide-free foods.

In 1951, again far ahead of the times, B.J. Palmer published a statement warning against the use of antibiotics. We knew that germs were not the cause of disease and we cautioned against the overuse of antibiotics decades before USA Today headlined their dangers in the 1990s. We also let our kids play in the sunshine (without toxic sunscreen) and in the backyard dirt, decades before the study came out saying exposure to animals and dirt is healthier than living in antimicrobial households. We insisted that symptoms should not be suppressed with drugs, but rather allowed to run their course while addressing the cause (which is actually the path of healing, not disease). When we questioned the use of vaccines (a practice rooted in mainstream, germ-phobic theories) we were further scorned for our blasphemous perspective.

We met other practitioners—naturopaths, homeopaths, midwives and herbalists, as well as parents who also understood these basic principles—and we rejoiced that there were others who were living from this logical but undermined paradigm. But we remained a marginalized group. Often ostracized, certainly ridiculed…and in some instances, violently opposed.

Understanding the Paradigm

The germ theory proposes that microorganisms are the overriding cause of many diseases. It was initiated by Louis Pasteur in the 19th century when he examined humans and animals that showed signs of being sick and found that they had very high levels of bacteria and viruses compared to those who were not sick. He then made the assumption that germs infect our body and cause sickness and disease. Pasteur, along with German physician Robert Koch, is considered one of the fathers of the germ theory. The practice of allopathic, conventional medicine to this day is still based on this theory.

Less known is that several of Pasteur’s contemporaries refuted his idea that germs cause disease. Claude Bernard, a colleague and physiologist of that era, resolved that the health of the individual was determined by her internal environment. “The terrain is everything,” he wrote; “the germ is nothing.” Other scientists tested Bernard’s theory. Elie Metchnikoff, a Russian immunologist a generation younger than Bernard and Pasteur, suggested that a synergistic interaction exists between bacteria and its host. He, too, claimed that germs were not the problem. To prove it, he consumed cultures containing millions of cholera bacteria; he lived to write about it, and didn’t even get sick.

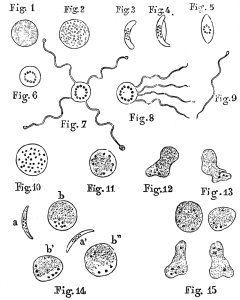

His contemporary, French chemist and biologist Antoine Bechamp, also believed that a healthy body would be immune to harmful bacteria, and only a weakened body could harbor harmful bacteria. His research contributed to this understanding when he discovered that there were living organisms in our bodies called microzymas, which essentially form into healthy cells in the healthy body and morph into unhealthy cells when the terrain is less than ideal. The conclusion: Germs do not invade us, but rather are “grown” within us when there is diseased tissue to live on.

Rudolf Virchow, another 19th-century scientist (dubbed the Father of Pathology), wrote, “If I could live my life over again, I would devote it to proving that germs seek their natural habitat—diseased tissue— rather than being the cause of diseased tissue; e.g. mosquitoes seek the stagnant water, but do not cause the pool to become stagnant.”

In this day and age, we have been taught that germs— bacteria and viruses—are bad, which ignores the vital functions they perform. They are designed to decompose dead and dying material. Germs are our planet’s recyclers; without them, life on earth couldn’t exist.

Out of the billions of bacteria and viruses we have in our bodies, most are considered “friendly germs.” Bacteria is essential for proper digestion and it scavenges dead cells in our body so they can be replaced by new healthy cells. When our body tissues become weak due to poor health management, normal bacteria and viruses start to multiply and scavenge our unhealthy, dying cells. Our immune system responds as a survival mechanism and we develop the symptoms of being “sick,” but the germs are just doing their job.

The question then becomes, what creates sickness and illness? Is it the germs or is it an unhealthy body? It has been said that on Pasteur’s deathbed, he admitted that Bernard was right and he, Pasteur, was wrong. Nonetheless, an era of antibiotic drugs, chemical pesticides and herbicides, vaccines and antibacterial soaps has ensued, resulting in a germphobic society and a pharmaceutical empire to lead the attack. But even worse, all of these weapons have interfered with the body’s natural microbiome and impaired our immunity.

Fast forward to June 2012, when the release of coordinated research from the Human Microbiome Project Consortium organized by the National Institutes of Health rocked the world. As The New York Times reported, “200 scientists at 80 institutions sequenced the genetic material of bacteria taken from 250 healthy people. They discovered more strains than they had ever imagined—as many as a thousand bacterial strains on each person. And each person’s collection of microbes was different from the next person’s. To the scientists’ surprise, they also found genetic signatures of disease causing bacteria lurking in everyone’s microbiome. But instead of making people ill, or even infectious, these disease-causing microbes simply live peacefully among their neighbors.”

Instead of the “one germ, one disease” theory that has dominated allopathic medicine for centuries, these findings imply that there is an entire ecosystem of bacteria symbiotically at work in the body, a concept understood by holistic practitioners for centuries. “This is a whole new way of looking at human biology and human disease,” says Dr. Phillip Tarr, a researcher and professor of pediatrics at the Washington University School of Medicine. “It’s awe-inspiring and it also offers incredible new opportunities.”

The following quote by Ronald J. Glasser, M.D., sums up the health crossroads we now face. This former assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota writes, “It is the body that is the hero, not science, not antibiotics…not machines or new devices. The task of the physician today is what it has always been, to help the body do what it has learned so well to do on its own during its unending struggle for survival—to heal itself. It is the body, not medicine, that is the hero.” As more doctors realize the self-evident principles of supporting the terrain, perhaps the allopathic model of killing the “bad” germs to fight disease may finally shift to improving the terrain to support the friendly bacteria.

The body, like all of nature, exists by maintaining a state of balance. It is dependent upon an environment that nourishes and nurtures with interconnectivity and cooperation between whole systems, and an underlying recognition of intelligence and a respect for the natural processes and order. Therefore, the essentials for a healthy terrain can be broken into several general premises: Nourishing the Terrain, Coordinating the Function and Trusting the Process.

Article originally posted at ICPA.org.